Only a handful of people can say “I’ve met the president.” Even fewer can say “I’ve met more than one president,” and Dimas Muhamad is one of them. He joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Kementerian Luar Negeri, or Kemlu for short) in 2014, and two years later started serving as one of President’s Joko Widodo (Jokowi)’s interpreters. Fast forward another two years, and here he is in Cambridge, Massachusetts, pursuing a Masters in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS).

Dimas, a Bandung native, has always had a passion for serving his country. His parents are both civil servants, and seeing his parents’ dedication to Indonesia motivated him to follow in their footsteps. To him, the work of a diplomat seemed to be the most interesting government-related work to him, so upon graduating with a Bachelor degree in International Relations from Universitas Katolik Parahyangan in 2013, he applied to work at Kemlu, and was accepted.

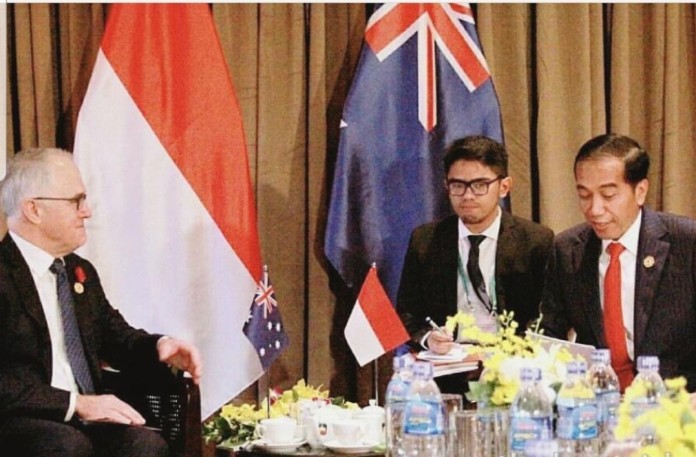

So, how did you become an interpreter for the president?, I asked. According to Dimas, all presidential interpreters originate from Kemlu after passing a training process. He took part in the training, and in the end was chosen to be an interpreter. Many of his social media followers ask him the same question, Gimana sih kok bahasa Inggrisnya bagus? (translation: How come your English is so good?) His English is almost accent-less that from just hearing him speak, I would have guessed he either lived abroad or grew up in an English-speaking household. But his answer is plain and simple: practice and hard work. “This is the first time I’ve lived overseas, and the first time I’ve set foot in the US. Nggak pernah les bahasa Inggris juga. (translation: I’ve also never taken an English course).” He comes from a relatively modest family, and it’s his passion for learning that has carried him far. “My point is that I’m not necessarily the best and brightest. … Di Kemlu banyak yang lebih fasih bahasa Inggrisnya dari saya dan mungkin dari keluarga diplomat. Tapi mungkin mereka juga nggak terlalu terdorong untuk ikut trainingnya dan akhirnya yang bahasa Inggrisnya lebih lancar tergeser oleh yang lebih semangat belajarnya. (translation: At Kemlu, there are a lot of people who can speak English better than me are may be from diplomat families. But perhaps they’re not as motivated to do the trainings and as a result, those who work harder end up getting selected over those who are better English speakers.”

Though he was enjoying his work as an interpreter, Dimas admitted that he has a growing concern for the country. He told me the story of of tahu and tempe (tofu and tempeh/soybean cake). They are to Indonesians like what fish-and-chips is to the British and what apple pie is to the Americans. A very Indonesian dish, yet the majority of its raw materials is imported. “It’s mind blowing! Tahu tempe is an integral part of our culture, yet we still import many of the raw materials. Yang orang-orang makan di warteg itu ternyata hasil impor. Gue gak habis pikir aja kayaknya ada kesalahan mendasar dalam manajemen ekonomi perdagangan industri kita. Kebijakan ekonomi kita kurang berpihak sama pelaku industri dan petani lokal. (translation: The food people eat street stalls are actually the result of imported products. I just couldn’t stop thinking how there must be a fundamental misunderstanding in the economics of our trade industry. Our economic policies aren’t in favor of the industry and local farmers.” And with that mindset, he decided to pivot from the world of international relations, diplomacy and official presidential interpreter to policy making.

Though he was passionate about policy, he realized that it was a completely new field for him. He didn’t have enough training and understanding of economic policies to pursue a career as a policymaker. This was what led him to pursue a Master in Public Policy at HKS.

What drew him to HKS specifically was the fact that it houses many leading development economists focusing on non-orthodox work, such as Dani Rodrik. “On paper, our economic policies are already aligned with what our economics textbooks tells us to do. For example, free trade. Our conventional wisdom on free trade is that it’s a good thing, and that it’s the road to prosperity. If we embrace free trade, our economics textbooks say we should be very prosperous. Yet if you compare us to other emerging economies, we have the lowest import tariffs. The fact that we are the exact opposite of what is predicted makes me think there must be something wrong. That’s what drew me here.” As he was explaining this, Dimas showed me an infographic from the following article in the New York Times: Building Trade Walls.

When asked to reflect on his three months at Harvard so far, he said that it’s been quite a change. “Gue dulu punya ekspektasi. Di Kemlu kan lumayan sibuk dan gue nganggap kuliah bisa lebih santai gitu. Tapi ternyata sangat berkebalikan dengan realitanya! (translation: I had this expectation before. I was very busy at Kemlu and I assumed graduate school would be more relaxing. But it turned out to be the exact opposite!”) He has learned a lot, but confesses to being overwhelmed with all the assignments and readings. His experience during undergrad was fairly relaxing, so he wasn’t expecting to be handed tens of pages of reading each day. He also wasn’t used to classes where students are expected and marked based on participation in classes. At the beginning, he always felt nervous when it came to raising his hand to contribute to the discussion, but overtime, he realized that everyone has a unique perspective to share. Though he felt behind at first, after speaking with other students in his class, he realized that he wasn’t the only one feeling overwhelmed. The workload is substantial, but it helps when you have a group of friends to study with.

He also admits to being disappointed with the Indonesian representation at HKS—there are only 6 Indonesian students in his class, out of almost 600 students. “That’s barely 1%. Ada kemajuan dari tahun sebelumnya, tapi we’re still so massively underrepresented. (translation: It’s an improvement from the previous year, but we’re still so massively underrepresented) Singapore has the exact number, padahal lebih banyak orang di Jakarta dibanding orang di Singapore.” His advice to Indonesians looking to study abroad is, “Coba aja dulu, jangan takut karena kami juga ngerasa banyak kekurangannya, tapi kami berani aja apply, dan Alhamdulillah diterima. (translation: Just try, and don’t be afraid because we also feel like we have a lot of room for improvement, but we were brave enough to apply and were thankfully accepted.)”

I left my interview with Dimas feeling more determined than ever. Through grit and perseverance, he has shown that anything is possible, whether it be studying at Harvard, or becoming an official presidential interpreter. You’ll never get what you want if you never try and work hard!

This article was written by Indira Pranabudi and edited by Azira Tamzil. Featured in this article is Dimas Muhamad. We also did a video Q&A with him which you can check out here. Here is his short bio:

Dimas graduated from Universitas Katolik Parahyangan in 2013 and started working as a diplomat in 2014. At the end of 2016, he was seconded to the office of the president’s private secretary to serve as one of the president’s interpreters. In August 2018, he moved to the US to pursue a Master in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.

[…] The Story of Dimas Muhamad, Former Interpreter for President Jokowi […]