Studying engineering and building satellites may just be a dream for many kids, but not for Ajie. In this article, he shares his story of how he got into engineering in the first place and how that led him to MIT, and to SpaceX’s Hyperloop competition.

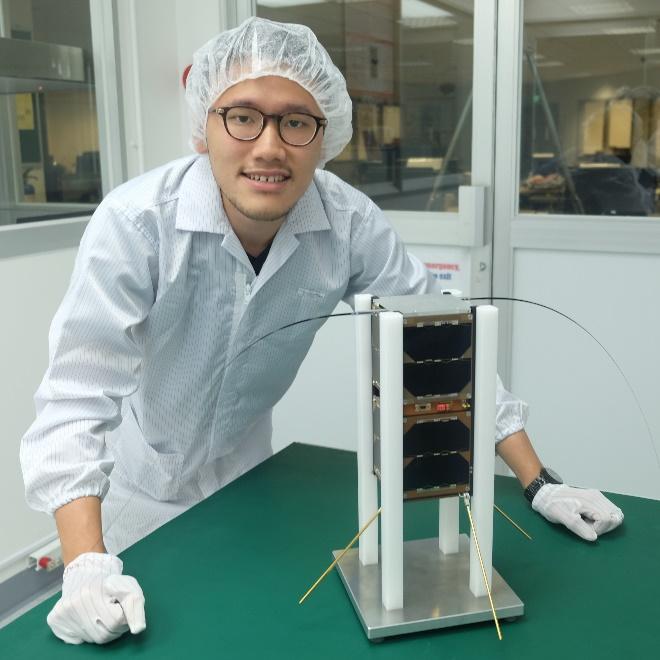

3… 2… 1… Lift off! My heart beat faster and faster as I watched the PSLV C-29 rocket lit up its engine and slowly rose to the sky from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota, India. The 40-meter tall, 200-ton rocket carried six satellites built in Singapore, and one of them was Galassia, a shoebox-sized satellite that my teammates and I at the National University of Singapore (NUS) had worked on for about a year prior to the launch. It took the rocket just about 20 minutes to reach its destination orbit of 550 km altitude (as a comparison, typical commercial planes fly at 10 km altitude). Once it was confirmed that Galassia had been deployed by the rocket, my teammates and I quickly rushed to our Mission Control room in NUS to prepare the ground station antenna and software, standing by until Galassia flew over Singapore, supposedly about 1.5 hour after its deployment in orbit. At an altitude of 550 km, Galassia flies at 27,000 km/h (that’s 80x faster than bullet trains!), making it pass above Singapore’s horizon for only about 10 minutes, 15 times a day. The first 10-minute time window was probably the most important 10 minutes of the mission. It would be the first time that we could confirm whether Galassia had successfully deployed its six antennas, charged enough batteries through its solar panels, and booted up its on-board control software.

It was roughly 10:18 PM, our ground station antenna started pointing to the sky and started tracking the curvature of the Earth. Based on our calculation and the information we received from the Indian space agency, that’s the time when Galassia would fly over Singapore for the first time. I sat in front of the radio as I tuned it to Galassia’s communication frequency. Everyone in the room stayed silent as we heard the radio starting to buzz, not receiving anything yet but noise.

“Beep…!”, all of a sudden, we heard Galassia’s beacon, the same sound we had always heard in our lab, but this time, from space. “Beep…!”, another beacon came from Galassia 30 seconds after the first. This time our ground station managed to decode the beacon and successfully displayed the satellite’s health data on the big screen. “Yeaaa!!!”, everyone cheered enthusiastically. That feeling for me was irreplaceable and unforgettable. Every single screw we tightened, every single component we soldered, and every single line of code we wrote, everything just fell into place in that single beeping sound coming from our baby satellite, hundreds of kilometers away.

This experience for me was a reminder that with engineering we can create something valuable out of nothing: something we can hear, see, feel, and most importantly, make use of. Engineering is a powerful tool for us to achieve new things that have never been done before and to move forward as a society. My first satellite, Galassia, wasn’t anything of global importance like the GPS or weather satellites that the world uses every day. It was merely a student-built satellite used for scientific demonstrations, with one being a spaceborne quantum entanglement experiment, which the general public won’t be able to benefit from until probably several decades from now. However, it was a beginning to bigger dreams. Since 2015, our research center in NUS, now called the Satellite Technology and Research Centre (STAR), has been working on at least 5 more satellites to be launched in the next couple of years, with a range of applications such as ground surveillance, precision agriculture, and maritime traffic and asset tracking.

Early Interest in Robotics

Just like most engineers out there, my love for engineering started early with LEGOs. Little did I know back then that it would lead me to making robots out of LEGO components and participating in national and international competitions. To me back then, making robots was a lot of fun and intellectually challenging. I knew I wanted to make useful robots one day, but my focus was drawn to merely proving that my team’s robot was the best in the competitions. In 2007 (I was 14), I participated in the World Robot Olympiad in Taipei. My team didn’t win any awards, nor did we even complete the challenge. However, it was still a life-changing moment for me as it was the first time that I competed not only for myself, but also with the Indonesian flag on my back. At that time I said to myself that Indonesia one day will be among the top in the field of robotics. I can still feel it today. It almost feels like a burning revenge.

From IoT to Wearables, from 3D Printers to Satellites

My experience in high school robotics led me to study Electrical Engineering. It wasn’t a difficult decision; I simply loved making something work, and I would love to make something useful one day. Throughout my 4 years of undergraduate studies and internships, I made various engineering products: a network of Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices to monitor the structural health of a building, a set of virtual reality (VR) headset and wearable for a whole new exercise bike experience, a 2-in-1 3D printer/scanner developed at a local Singapore startup, and lastly the Galassia satellite. I also did personal DIY projects in my free time, for example, I built a custom Segway from scrapped electric wheelchair and a power bank for my own daily use. Again, I did all these mostly for fun, but they showed me that engineering opens up so many possibilities. These experiences will be my building blocks for me to one day finally pursue the one thing that I will proudly call as my career. At least that’s how I hope it would work out.

Coming to MIT

So far, I might sound like I have figured my life out and I know what I want to do. Well, you’re wrong :p. I was again faced with the quarter-life crisis. If you are on the same boat as I am, high five! I know being lost and confused sounds somewhat immature, but I’d like to think that this is all normal and a part of growing as a person (hashtag growth mindset). Anyway, what do millennials do when they don’t know what to do with their life? Apply to grad school! Yes, that’s what I did.

Pro-tip: do not say you don’t know what to do with your life in your application essay to grad schools.

I must be honest, applying to grad schools has been one of the most emotionally draining experiences in my life. It was very intimidating, especially the application to the program I’m interested at MIT. I applied to MIT’s System Design and Management (SDM) program, a master’s program that is jointly offered by the School of Engineering and the Sloan School of Management. It is a prestigious program mainly designed for mid-career professionals who aspire to be engineering/technical leaders. Quoting from the admissions page: “The typical SDM student is an engineering professional in his/her mid-30s (range 25-50+) and has 10 or more years of work experience (range 3-20+).” I was 24 with 2.5 years of post-undergrad experience when I applied and I had very low, close to zero confidence of getting admitted. I told myself it’s okay if I didn’t get in and that I could still try again sometime in the future. I even let myself miss the first application round’s deadline because at the time I still thought that I had no chance at all. To my surprise, I got in. So for those of you who like to doubt yourself, well, think again 🙂

I came to MIT SDM with one intention (aside from the perks of getting to experience four seasons and a bunch of road trips in the US, of course!), I want to learn to be a good engineering leader. I know my own hands are not enough. The only way for me to make an impact at a large scale, I believe, is to have a strong team and the ability to lead that team toward the right goal.

Through MIT SDM, I was trained to be a systems thinker: someone who solves problems by delving into the details without losing the holistic view or the big picture, a trait that is important to have for engineering leaders. A lot of the examples discussed in the class were taken from space missions, where risks are high, a huge sum of money are at stake, and the systems and projects became uncontrollably complex so as to deal with the harsh environment. As an ex-satellite engineer, I was of course happy to see all these examples. However, the principles and methods we learn at SDM is applicable to all kinds of industries, much more than space. Throughout Spring 2019, I worked with Mitsui OSK Lines, a company sponsor which is also one of the biggest maritime shipping companies in Japan and in the world, to explore the idea of digitizing the container ship market, which is a huge and very complex industry with many different stakeholders and long chains of processes in place.

In my opinion, the school is a safe place to fail and to try different things. This thinking brought me into joining activities outside the class. Toward the end of my first semester, I joined the MIT Hyperloop team to participate in Elon Musk’s annual SpaceX Hyperloop Pod Competition. I learned a lot on how to deal with great complexity in a short time span. And most importantly, I learned a lot working with people from different background and culture. Through ups and downs, our team managed to finish 1st among the US universities and 5th worldwide, in addition to earning an Innovation Award from SpaceX. It was indeed a blessing.

We Need More Engineering Leaders in Indonesia

Engineering moves us forward. And if we want to thrive as a society, we need more engineers in Indonesia. We might get by feeding our kids on all the natural resources and commodities we have, and we might survive the next century selling our well-known hospitality to the world through the almost unlimited beautiful islands in our country. However, we cannot merely rely on these. Put it in a harsh way, we can’t stay being “victims” of exploitation and we can’t just keep being “guinea pigs” of other countries’ products. Commodities are exported from our country only as a means for us to “consume” it back, but at a much higher price. There is a strong correlation between industrial output and overall economic growth of a country. Just look at the economic superpowers in the world like China, USA, Japan and Germany. A key component to that, I think, is engineering know-how.

I’m not writing this article to be down in the dumps though. We all know we are far from setting our foot in the “elite club”, but we have also come quite a long way in building homegrown engineering products and talents. Take Dirgantara Indonesia (Indonesian Aerospace) as an example. Since 1976, they have exported 48 aircrafts to various countries including Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, UAE, Senegal, Pakistan and South Korea. Or take a more recent example, Octagon Studio. Since 2015, they’ve had over 2-million app-downloads and sold over 1-million products in more than 50 countries worldwide.

What about the space industry? Not many people know, but we do have our own space agency! Since mid 2000s, the Satellite Technology Center at Lembaga Penerbangan dan Antariksa Nasional (LAPAN) has been developing at least 5 satellite programs in-house (three are already in orbit). They have also been developing rocket technologies, with sounding rockets being launch-tested regularly in West Java as a groundwork for orbital launch vehicles. Isn’t that cool?

LAPAN’s newest Mission Control Centre in Bogor

This is all to say that we, Indonesians, have what it takes to become a technologically capable, developed country. And in order for us to get there, we need more engineering leaders who can make dreams like Dirgantara Indonesia, Octagon Studio, and LAPAN possible. As what our late father of technology, BJ Habibie, said: “Why should we have our own, homegrown aircrafts? The most important reason is for the sake of growing our children’s knowledge. So that it can be a building block for the advancement of technology in this country.”